“There will be hardship for us all. For you, in particular. I will not allow you your petty corruptions. I will denounce your shameful alliances. If you fall into heresy or allow heresy to flourish, if you fall away in schism, I will fire you, excommunicate you formally with bell, book, and candle. If you oppose me, I will fight you tooth and nail. I will not permit any use of politics. Any use. I will require a strict accounting from you about money, about doctrine, about moral practice. I will not treat the Church’s enemies as friends or even as decent people. And I will not yield to the economic boycott of the financial squeeze of the Universal Assembly.”

-Richard Lansing, fictional papabile, addressing the College of Cardinals in Conclave (Vatican, page 823)

Hopefully, you did not skip the fictional opening quotation above. Imagine if we had that kind of pope even once or twice over these past hundred years. That was the assertive verbiage of Malachi Martin’s main protagonist in Vatican (1986), an effective fiction/faction prequel to Windswept House. It presents readers with an almost exhaustive exploration of Church politics, including the papacy, from 1945 to the mid-1980s.

It will be impossible to provide the “Cliff Notes” version of this story without spoilers, so consider that if you wish to read the book yourself. Its author, Fr. Malachi Martin, yet again showcases himself as the last apostle of the pre-Internet age by delineating the global spiritual crisis we’ve faced since WWII. He shows us, as I’ve explained elsewhere myself, how the Catholic Church and Western Civilization have become prey to a global network of evildoers.

On the surface, these diverse foes manifest as a disparate motley crew of left-wing communists and right-wing fascists. However, we discover how they operate under the control of one semi-invincible entity, a dreaded primary instigator. They possess a singular objective of destabilizing the Church from every angle: modernist infiltration of the hierarchy, corruption of governments and economic institutions, and the development of super-destructive weapons.

Of course, the novel also covers the entire Vatican II saga — that massive takeover by anti-Catholic forces who subverted the dwindling traditional hierarchy following the death of Pope Pius XII.

NOTE: Before I begin my analysis, don’t forget to check the cheat sheet with all the character code names and real names, appended to the end of this post. Just like in Windswept House, Fr. Martin created nicknames for real-life clergy and secular figures. This review will focus on the characters’ real names, though.

Table of Contents

- The Bargain – Rome’s Compromise with the Lodge

- Who’s In Charge of Global Evil? – The P1/P2 Theory

- The Disastrous Vatican Finances

- Several Betrayals & Assassinations

- The Lamentation of Many Popes

- Parallels with Windswept House

- Parallels between Richard Lansing and Malachi Martin

- Conclusion

Appendix: Character Code Names vs. Real Names

Now, let’s review . . . Vatican!

1) The Bargain – Rome’s Compromise with the Lodge

Background for “The Bargain”

Although the story does not begin in 1870, it is essential to have a cursory understanding of that watershed year, when the Church lost Her temporal territories to Freemasonic forces. It was the so-called Italian reunification, which resulted in secularists conquering the Vatican, rendering the pope a prisoner in that tiny enclave.

I won’t rehash the entire history, and neither does Fr. Martin, but it was these desperate circumstances that led the Roman hierarchy to strike a “bargain” with the Freemasonic Lodges. Rome did so to maintain its existence and develop a new political and financial structure, which it received permission to do, provided it did not infringe upon the Lodge.

What did this dubious Bargain entail?

- Every pope signed the Bargain from 1870 through the 1980s.

- Freemasonic (“Universal Assembly”) representatives were also signatories.

- This is the specific text of the Bargain:

- “The Universal Assembly guarantees the Holy See all the facilities, easements, favors, privileges, and equality now enjoyed by members of the Assembly.

- ‘The Holy See guarantees that every act of access to such facilities, etc., will be taken only over the signature of one man: the eldest male issue of the same family in each generation, and known to the Universal Assembly. Also guaranteed: two prelates from the Holy See’s Secretariat of State, not lower than Monsignore in rank, will be formal members of the Lodge.”

- The Bargain involved a “keeper,” one individual from the same family (the fictional De La Valles), who reserved the power to veto certain Church actions and protect the papacy. Each generation, a new De La Valle held the position of keeper or “maestro.” This man would devote most of his time to proliferating Vatican finances amid an increasingly usurious world economic system. The keeper could even intervene against the Roman Pontiff if that pope ever jeopardized the Church (as Paul VI did with the Vatican Bank debacle). He also got to supervise the proceedings of every papal conclave from a secret room within the Sistine Chapel.

- The Bargain included a stipulation whereby the Vatican would keep two emissaries as Lodge members to maintain relations. The book states that both Monsignor Annibale Bugnini and Archbishop Giovanni Montini (the future Paul VI) were delegates to the Lodge.

What is the greater significance of this Bargain? Although I have no evidence of a literal pact between Rome and Freemasonry, it is not unreasonable to suggest the upper hierarchy got itself into trouble this way. This may not have involved a specific contract, but it isn’t far-fetched to assert something along these lines may have occurred.

Recall, for example, the heavy emphasis on diplomacy under good popes, such as Popes Leo XIII, Pius XI, and Pius XII. These men, well-intentioned as they were, prioritized negotiation and handshake deals rather than exerting their authority as God’s Vicar on Earth.

This would spill over into the affairs of secular men as well. The book details several social, political, and economic moves Catholics took to combat the modernists, Freemasons, communists, and fascists. Examples include the failed “Catholic Action,” the development of the Vatican Bank, cooperation with various mafia groups, and other fruitless (or worse) activities.

Then, consider all the “races” since the 20th century, which embody the rejection of spiritual power, both in the Church and throughout the world. This includes the nuclear, finance, military, and now AI races. Everyone assumes we must win these contests, almost by any means necessary, or we’ll all face oblivion. To this day, we witness this cowardly mindset as the SSPX bargains with apostate Rome to keep itself in “good standing” with a now non-Catholic hierarchy.

At any rate, neither secular Catholics nor the hierarchy seemed to trust God’s providence. Everyone has defaulted to naturalism, realpolitiking, and bargaining.

2) Who’s In Charge of Global Evil? – The P1/P2 Theory

The next crucial theme in Fr. Martin’s book involves his framework for understanding this nefarious “Universal Assembly,” which assumes many shapes and forms, some more enigmatic than others. However, to say “it’s just the Freemasons,” would be myopic. Instead, during the course of the book’s events, the good Roman prelates began to discover that their opponents originated from numerous influences and ideologies.

The clergy could not, however, pinpoint the ringleader. Was it the Italian Lodge? What about the various Protestant sects? Could it have been left-wing terrorists, Liberation Theologians, or the Soviet Union? A definitive answer would elude the Church for decades.

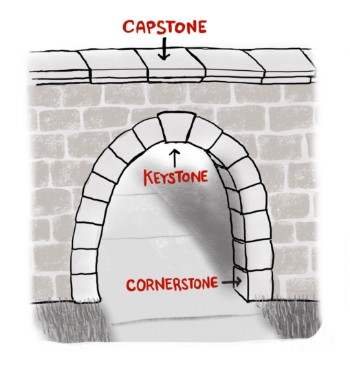

One curial bishop created a framework for understanding the Church’s global opposition by likening it to an arch with its two long sides and keystone or capstone at the top. He called it the P1/P2 theory.

P1, the arch’s keystone, represents the greatest powers in the world: globalist supermen, largely unknown to the public, incredibly wealthy with stealth influence everywhere. The P2s are the disparate ancillary groups: mafias, different lodges, vicious terrorists, the USSR, other rogue nation states, and so forth. The “P2” designation is also a play on the name of the Freemasonic lodge, Propaganda Due (P2), which gained significant control over Vatican finances.

What is the mission of this perfidious network?

The ultimate goal of the P1/P2 network is to engender DESTABILIZATION throughout the Catholic Church and Western Civilization by any means possible. This includes economic disturbance, political upheaval, assassinations, espionage, nuclear weapon development, and much more. In a Catholic sense, this would include Liberation Theology in Latin America, the Soviet takeover of Eastern European churches, and infiltration of the Church’s structures and liturgy.

What are the other specific P2s discussed in the novel?

- The Northern Alliance – This collection of mostly Protestants (from different denominations) was intent on getting “their guy” on the Throne of Peter, thereby extinguishing the dreaded, old “Romanism” they despised. This group held connections with Annibale Bugnini and Giovanni Montini, who seemed sympathetic to their revolutionary aims. There is some implication that members of this group may have worked with Bugnini to construct the Novus Ordo Mass.

- The Red Brigades – This was a real-life left-wing terrorist group, active in the 1970s and 1980s, infamous for kidnappings and murders. The group’s targets were wealthy and influential figures in Europe. It even had a penchant for murdering the children of prominent politicians and leaders to intimidate them into inertia.

- Gustavo Gutierrez (code-named “Jaime Herreras” in the book) and Liberation Theology – The novel focuses on Liberation Theology extensively, including its origin as a purely Soviet invention. Its primary leader, the fictional Fr. Jaime Herreras, SJ, seems to be the book’s version of Gustavo Gutierrez, but I can’t say so 100%. Herreras, who also aligns himself with the Northern Alliance, devotes his time to spreading a materialist gospel throughout Latin America.

Who runs the whole evil operation? Was it the same cabal of villains from Windswept House?

Vatican doesn’t mention all the same figures from Windswept House, but there is plenty of continuity. Windswept House even features a shadowy “Capstone” villain, who dictates orders to the Concillium 13, a consortium of prominent business leaders. So, Fr. Martin has used the keystone/capstone analogy in different books to signify the same thing.

His 1986 novel, Vatican, doesn’t include specific folks like Klaus Schwab or Ted Turner, but it briefly mentions something called the Lotos Group, headquartered in California. Perhaps this is equivalent to the Bohemian Grove or the Bilderberg Group. The book does not elaborate on this sufficiently, though. It leaves a certain degree of mystery in identifying the real kingpins leading the assault against the Catholic Church.

With that antagonistic framework in mind, let’s explore the various ways the P1/P2 forces manipulated the hierarchical Church, including several popes.

3) The Disastrous Vatican Finances

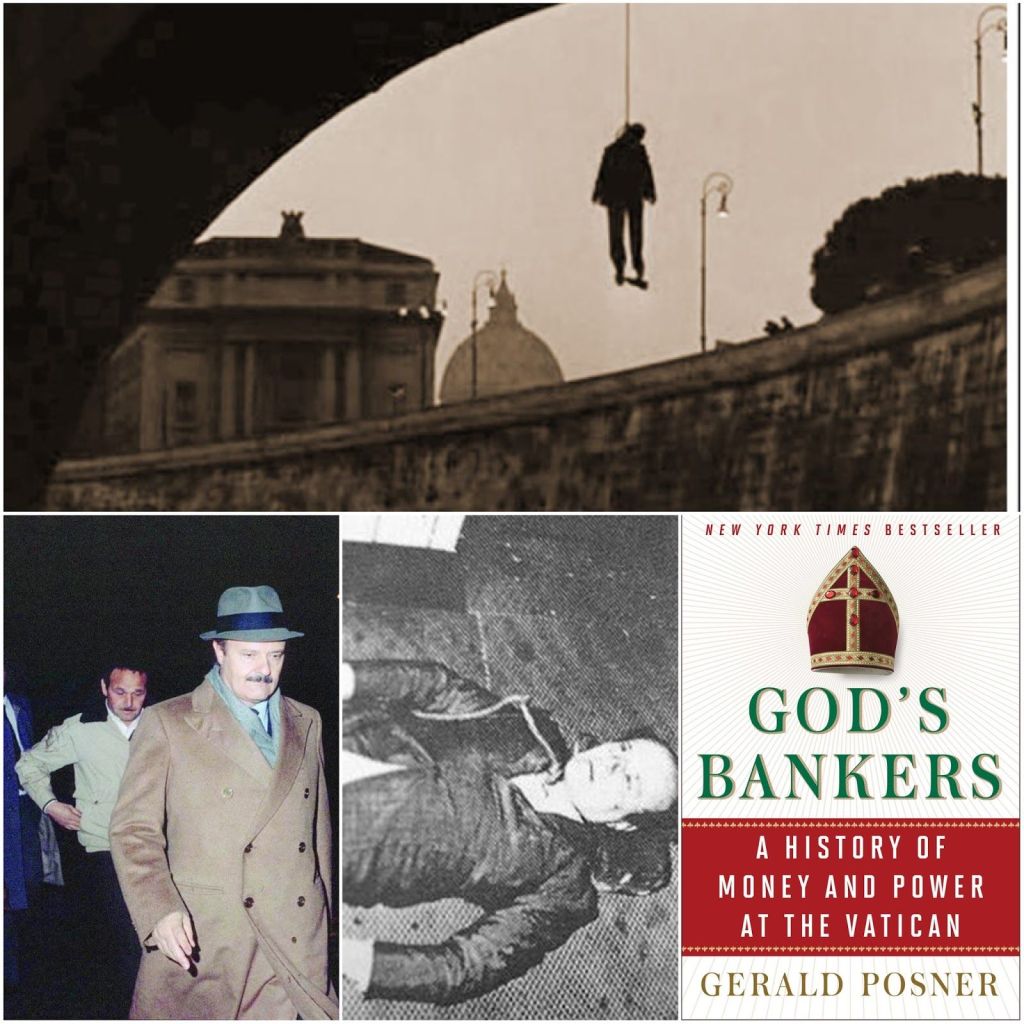

Many who attempt to read this lengthy novel may find its descriptions of Church finances rather dense and complicated, but they are jarring and relevant. You cannot tell the entire story of Rome’s collapse into modernism without mentioning its entrapment by surreptitious bankers like Michele Sindona and Roberto Calvi.

As I alluded to in a previous section, it was Pope Paul VI who plunged the Vatican Bank into Italian “dirty money” by handing its keys first to Sindona. The man known in real life as “The Shark” had actually been a supporter of Giovanni Montini when he was Archbishop of Milan, according to Fr. Martin’s narrative.

Sindona eventually finished his criminal finance career by getting caught by the U.S. for money laundering, but not before squandering billions of Vatican dollars. Paul VI then unwittingly hired Roberto Calvi, who did much of the same, before earning his destiny secured to a large noose (see photo below). These are the sorrowful consequences of the Vatican’s multi-decade strategy of playing the world’s games and embroiling itself in the Jewish-dominated global financial system.

Keep in mind that billions of wasted dollars in the 1960s and 1970s were the equivalent of hundreds of billions (or more) in today’s terms. Of course, this was also when the Church hemorrhaged priests and religious (thanks to Vatican II), and ruined its lay donorship by chasing millions from the Church. Whatever financial gains they sought through “prudent investment” would eventually dwindle into a massive deficit years after acquiring a windfall inheritance from Mussolini.

The Vatican’s acquisition of blood money (from Italian fascists) was destined for disaster, worsened by its choice to entrust it to even greater miscreants (Sindona, Calvi, et al.). This was the most predictable result of the Roman hierarchy’s decision to neglect the value of its sacramental economy in favor of the world’s satanic economy.

4. Several Betrayals & Assassinations

Given that the novel involves no shortage of espionage and treacherous double agents, you will find many betrayals and assassinations throughout its 800+ pages.

This includes a story about a Soviet operative who infiltrated the Vatican pretending to be a priest. This Soviet sneaker tricked several in the Vatican State Department, gained valuable information for the USSR, and caused the deaths of about a dozen Vatican counteragents/missionaries in eastern Europe. He would later rise to a prominent Kremlin position as the fearsome “General Control.”

Here is a list of other assassinations and betrayals covered in the novel (though I’m leaving out at least a couple).

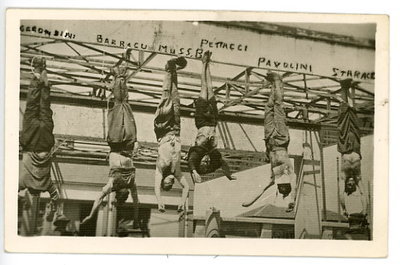

- Benito Mussolini – Although nobody cried for him except his mistress (who suffered the same fate), Pope Pius XII knew this assassination would plunge Italy into a state of chaos. He wasn’t altogether wrong.

- Pope John XXIII (attempted) – The Roman Pontiff, who was ill from the beginning of his pontificate, almost succumbed to a Soviet-led assassination via odorless nerve gas. The USSR paid a curial priest to get close to the pope for this task, but was intercepted, ironically, after a tip from Russian Orthodox Metropolitan Nikodim Rotov.

- Pope JPI (one attempted; one successful) – Today, many folks realize Pope JPI’s death wasn’t from natural causes. Fr. Martin’s narrative includes first a failed assassination attempt with Metropolitan Nikodim as the would-be assailant. In real life, the Metropolitan actually died at Pope JPI’s coronation. In the book, the conflicted Russian Orthodox prelate was supposed to meet with the pontiff to deliver a gift filled with nerve gas. However, Nikodim, having experienced remorse over his intentions, performed a heroic sacrifice by opening the gift, thus exposing himself to the lethal nerve gas. Pope JPI realized what had happened and gave Nikodim absolution just before he expired. Shortly thereafter, the Russians re-attempted a similar attack and were successful.

- Roberto Calvi – Calvi met his infamous and well-publicized fate much like any admiral from Star Wars after “failing” Darth Vader (or the Lodge) for the last time.

- Pope JPII – In this book, JPII didn’t survive his 1982 assassination attack. The story narrative is similar to the real-life events. However, the first responders purposefully transported the pope to the wrong hospital, one lacking the emergency blood storage he needed, leading to his slow and painful demise within months. This resulted in yet another conclave and the election of a new fictional pope with a different point of view on dealing with the world.

5. The Lamentation of Many Popes

Fr. Martin gives what I would call a rather generous perception of the popes in this period (Pope Pius XII through JPII). He does not withhold his criticisms, especially regarding Paul VI. Even for that pontiff, however, he grants the benefit of the doubt, even suggesting that the Vatican-II pope regretted his failures toward the end of his life.

The novel demonstrates how each pope died with several regrets. Their failures involved the mishandling of communism, secularism, modernism, and NOT countering the world’s evils with the spiritual power of their office. Here is a synopsis of each pope’s lamentations:

- Pope Pius XII (1939 to 1958) – He was indisputably the best portrayed pope in the novel by any measure. Whether we consider spiritual leadership, geopolitical savvy, economic comprehension, or doctrinal purity, this pope was the best of them after Pius X. However, his lamentations were that he relied too much on his skills derived from many years as Secretary of State rather than the full authority of his office. He was well aware of the implications of Our Lady of Fatima and had no trouble forecasting the ominous Soviet encroachment. Yet, although he announced the glorious Dogma of Mary’s Assumption, he never performed a proper consecration of Russia to Her Immaculate Heart. The novel recalls his final days languishing at Castel Gandolfo, wishing he had taken different measures during his pontificate and cardinalate.

- Pope John XXIII (1958 to 1963) – Fr. Martin calls him “Papa Angelica” in the novel, referencing his perceived seraphic commitment to usher in an era of greater love throughout the Church and world. What Pope John XXIII lacked in administrative savvy, he compensated for with his amiable and fatherly demeanor. However, the book has no choice but to spend most of its narrative on the pope’s leadership naivety. Although the pope may have opened the council with good intentions, he clearly lacked the skill to manage it, leading to its hijacking by modernists. He realized his shortcomings once the council began while observing its chaotic proceedings from his sickbed in 1963.

- Pope Paul VI (1963 to 1978) – Some of Malachi Martin’s other novels were much more critical of this pontiff, but you could say Vatican gives Pope Paul VI a reasonably fair treatment. He’s borderline detestable to any traditionalist for the first 12 years of his pontificate before finally coming to his senses after contracting leukemia. By then, he realized the error of shunning the “old guard” of prelates from Pius XII. However, this was well after losing control of Vatican II, the formation of the Novus Ordo Mass, massive financial turbulence, and other modernist innovations all over the Church.

- Pope John Paul I (1978) – The novel portrays this pope as the most traditional and orthodox following the Pius XII pontificate. The College of Cardinals realized, after so many sorrows and scandals under the previous two pontificates, that it needed to course correct back toward tradition. Granted, I’m not so certain Pope JPI was truly the gold standard of tradition, as the novel depicts him. The late Fr. Hess had a different point of view, believing he was not one of the worm-ridden popes prophesied at La Salette, but also no champion of orthodoxy. Of course, this pope did not last long enough to prove or negate this. The book delineates his assassination, orchestrated by the Soviets, forcing the Church to elect a new pontiff within a month of his election. There is also some implication that high-ranking prelates, like Cdl. Jean-Marie Villot, were privy to the assassination plot.

- Pope John Paul II (1978 to mid-1980s) – Fr. Martin’s book created an alternative ending to the JPII pontificate, featuring the active and amiable pope’s death by assassination. Although Pope JPII received a somewhat favorable depiction, Martin also characterized him as overly optimistic about Church-secular cooperation, tarnished further by his approval of Vatican II novelties. Martin seemed to imply that JPII would have been more successful had he employed the same zeal from his days as a heroic figure in Poland. Although in the book he did not get the chance to do this. However, we know that in real life, JPII would suffer another 20 years of imprisonment in ecumenical, apostate Rome, where he would accomplish little reform through endless diplomacy and travels. Many would say things only worsened much further.

The book culminates with a newly elected pope, Richard Lansing, the fictional cardinal en pectore, who succeeds JPII after the latter succumbs to gunshot wounds and hospital poisoning. The new Pope Lansing explains how these popes regretted their handling of fascism, communism, and all the other encroaching secular evils. This is the story behind the opening quotation at the beginning of this review.

The book abruptly ends with Pope Lansing’s election after his stirring speech, where he destroyed the “Bargain” document, vowing to end all negotiation with the world on its wicked terms. The new pope also insisted on maintaining a lengthy list of like-minded successors willing to succeed one another as martyr popes, not unlike the early Church.

Regrettably, this part is only fiction, what Fr. Martin or any decent Catholic would have liked to have happened, but we all know how things transpired otherwise. Now that we have the gist of the book’s narrative, let’s examine a few parallels between Vatican and Fr. Martin’s other famous novel.

6. Parallels with Windswept House

Since I would assume readers are more familiar with the popular Windswept House novel, I’d like to cover some interesting parallels between that novel and its prequel, Vatican.

- Both deal with the difficult encroachment of modernism since 1870. In Vatican, the Bargain begins that year. However, in Windswept House, this was also the point where the owners of Windswept House (located in Galveston, TX) earned special privileges with the Church in Rome. The book’s protagonist, a traditional priest, grew up there and played a crucial role in helping Pope JPII combat the modernist hierarchy and secretive “Concilium 13.” Each story involves a fictional traditional American priest who performs undercover duties to assist Rome.

- Both begin with a horror story. In Windswept House, the narrative starts with the most horrifying depiction of a black mass, filled with ritualistic rape, and the enthronement of Rome to Lucifer. You can read my review of that book to learn more, but it takes place in 1963, whereas the rest of the novel covers events after 1978. In Vatican, the corresponding horror story is the end of WWII in Italy, where its dictator Mussolini suffered execution by firing squad and a hideous public display of his corpse. Following that brutal tyrannicide, Fr. Martin described the testing and eventual deployment of the nuclear bombs used to attack Nagasaki and Hiroshima. The massive bomb testing achieved enough instant luminosity to “out-sun the sun” with its sky-consuming detonation. This happened, ironically, at the Trinity Site in New Mexico at the precise moment Pope Pius XII offered benediction for the Feast of Our Lady of Mt. Carmel.

- Both books begin with an ominous warning from Pope Pius XII (both related to financial entanglements and growing evil powers in Europe and worldwide). His Holiness understood well what awaited us but felt powerless to intervene.

7. Parallels between Richard Lansing and Malachi Martin

I also noticed some parallels between the book’s author, Malachi Martin, and its primary hero, Richard Lansing. It was almost as if Fr. Martin tried to insert some of his experiences into the character. Here are some examples.

- As you may know, Malachi Martin was the assistant to Cardinal Augustin Bea, SJ, who played a significant role in the novel. After WWII, when Msgr. Lansing was in charge of issuing special Vatican passports to refugees, there was one incident where he encountered Nazis seeking passports to escape to Argentina. Lansing refused them as any morally sound person would do before discovering that all the higher-ranking prelates had already signed off on the Nazi passports. He reported this disturbing finding to Fr. Bea (Fr. Lanser, in the book), but received a cold, realpolitik-style reply. Apparently, the pope had already arranged for the Nazis to receive their passports after a previous deal/favor. Granted, it was Bea who explained this to Lansing, seeming almost dismissive of the moral implications of helping several Nazis flee to South America. One can’t help but wonder if the real-life Malachi Martin ever experienced anything this scandalous while working in the curia, particularly under Cdl. Bea. Imagine what treachery Martin had to ignore or avoid by the time Vatican II began, especially considering that Bea was a major contributor.

- After several years as a bishop and secret operative for the Vatican, Richard Lansing became a cardinal in pectore (unknown to the public). Fr. Martin explained this as Pope Paul VI’s end-of-life realization that he trusted the wrong prelates (like Bugnini) and needed help from a genuine traditionalist. However, Fr. Martin himself was thought to have been a secret bishop, according to some rumors. Was this Martin’s way of offering a nod to that theory despite his dismissal from the Jesuits? Some sources say that he, like his character, Richard Lansing, was a bishop who ordained priests covertly throughout the underground church in Eastern Europe.

- There is also a minor subplot in the book where an unscrupulous journalist launches false accusations of Bishop Lansing having an affair with another man’s wife. This incident doesn’t seem to have much bearing on the rest of the story, but it reminds me of some of the baseless accusations cast against Fr. Martin. Most of Martin’s accusers were opportunistic, dishonest journalists as well. Nonetheless, could Martin have tried to pre-empt some of his infidelity accusations with this side story about the journalist black-mailing Richard Lansing? You would have to read about it and compare it to some of the frivolous accusations to understand the context, but I believe Martin may have telegraphed a few things.

- I’d like to make one last comment regarding Cdl. Augustin Bea, who allegedly had an important hand in the drafting of the odious document, Nostra Aetate. Fr. Martin’s overall portrayal of Bea is surprisingly positive, either out of respect for his former boss or because the pope compelled Bea to write the things he did. The novel explains how Paul VI insisted Bea write a comprehensive ecumenical essay, which would come to be known as the “Jewish Document.” The dialogue between Bea and other conservative prelates (like Cdl. Ottaviani) reveals his dread and apprehension over such an assignment. In the novel, he anticipated the “crucifixion” he would receive from all sides (traditional Catholics, Jews, etc.) regardless of whatever he produced. All in all, Vatican makes Bea look much more favorably toward the end of his life. In fact, it was he who lectured Pope Paul VI, from his deathbed, over the suicidal trajectory he set for the Church.

Conclusion

I hope this brief analysis of Fr. Martin’s terrific novel encourages you to read the book yourself. While it requires a substantial investment of reading time, it would be worth it to supplement your knowledge of Church affairs, especially if you already got through Windswept House. I would say the novel’s contents also correspond with the geopolitical and Church matters Fr. Paul Kramer expounds in his book, The Mystery of Iniquity.

Since most of Martin’s claims from the 80s and 90s only appear more obvious in the 2020s, I recommend responding to the Church’s near apostasy with dedicated prayer. Perhaps we could have averted such lamentations had any one pope consecrated Russia to the Immaculate Heart of Mary.

We also could have harnessed more spiritual power by following the Blessed Virgin’s command to pray the Rosary every day (all 15 decades). Let us do so now, better late than never, with the special intention that God would send us a holy pope to lead the Church out of its current eclipse.

Appendix: Character Code Names vs. Real Names

- Papa Profumi – Pope Pius XII

- Papa Angelica – Pope John XXIII

- Papa Da Brescia – Pope Paul VI

- Papa Serena – Pope John Paul I

- Papa Valeska – Pope John Paul II

- Cardinal Arnulfo – Cardinal Alfredo Ottaviani

- Cardinal Lanser – Cardinal Augustin Bea

- Cardinal Falconieri – Cardinal Carlo Confalonieri

- Cardinal Cerbin – Cardinal Joseph Bernardin

- Cardinal Rollinger – Cardinal Joseph Ratzinger

- Archbishop Eduardo Lasuisse – Archbishop Marcel Lefebvre

- Cardinal Buff – Cardinal Basil Hume

- Cardinal Levesque – Cardinal Jean-Marie Villot

- Cardinal Casaregna – Cardinal Agostino Casaroli

- Monsignor Sugnini – Archbishop Annibale Bugnini

- Paolo Lercani – Michele Sindona “The Shark”

- Robert Gonella – Roberto Calvi “God’s Banker”

- P2 → Propaganda Due or Problem Two, a Fascist Freemasonic Lodge

- Brother Reginald of Zaite (Northern Alliance Member) – Brother Roger Schutz of Taizé

- Banco Agostiniano – Banco Ambrosiano

- Benjamin National Bank – Franklin National Bank